Cape Town social housing — the city has a comprehensive long-term strategy

28-06-2021

Read : 481 times

Daily Maverick

Source

In a recent Daily Maverick article, “The location of social housing in Cape Town: Separating fact from fiction” by Andreas Scheba, Ivan Turok and Justin Visagie (21 April 2021), the researchers drew incorrect conclusions about what constitutes well-located housing in Cape Town, and present an incomplete picture of the metro’s social housing pipeline.

For instance, it is incorrectly indicated that planned social housing projects for Cape Town’s inner city currently amount to around 240 units at the Pine Road development in Woodstock.

While the extent of inaccurate data for other metros is unknown, the facts in relation to Cape Town are as follows:

There are approximately 2,000 social housing units already in the pipeline for the inner city and surrounds, with ongoing exploration of further opportunities related to different projects at various stages.

This figure relates only to municipal-driven projects, and excludes other forms of affordable housing driven by the city and private sector, as well as any provincially driven projects.

Selected projects at various stages include:

- Projects nearing construction phase include Pine Road (about 240 social housing units) and Dillon Road (+/- 150) in Woodstock; Salt River Market (+/- 200); and Maitland (+/- 200);

- Projects undergoing land use management processes to be made available for social housing include New Market (+/- 300); Pickwick (+/- 400); and Woodstock Hospital precinct (+/-700);

- Woodstock Hospital has favourable conditions for development, but has been delayed by an orchestrated building hijacking in The city is currently pursuing the correct legal route to unlock social housing at this site;

- Potential projects at early feasibility stage in the inner city pipeline include Fruit and Veg (150 units); and

- Western Cape Government-driven projects, supported by the city, include the Conradie development in the inner city feeder suburb of Pinelands, Founders Garden, Foreshore Precinct and Helen Bowden Nurses Home in Green Point (subject to a building hijacking by the same grouping). All have significant potential for social housing unit yields.

The above list of city projects speaks only to the part of Cape Town that may be regarded as the inner city and surrounds.

The metropolitan area, in fact, consists of various important economic nodes, including Century City, Tygervalley, Mitchells Plain, Khayelitsha, Phillipi, Atlantis, Somerset West and Cape Town’s second CBD and major public investment project, Bellville.

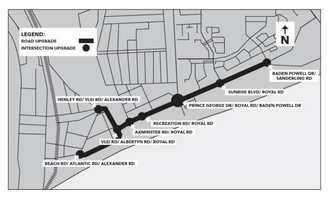

The Voortrekker Road corridor, which links the CBD to Bellville, is being spatially targeted to expand economic opportunity by creating the enabling environment for business activity, jobs, affordable housing and public transport.

A total of about 2,500 social housing units are either nearing completion or about to commence construction, either along the Voortrekker corridor or near the aforementioned economic nodes. A further estimated 1,200 social housing units are currently in the city’s planning pipeline for these areas, with more to be added in time.

Social Housing Projects in the aforementioned areas are:

- Recently concluded projects, in partnership with the Western Cape government and Social Housing Regulatory Authority (SHRA), include Weltevreden (+/- 100 social housing units), Bothasig Gardens (+/- 300), and Glenhaven (+/- 500), with its final phase nearing completion;

- Projects nearing construction phase include Goodwood (+/- 1,000), Heideveld (+/- 180) and Elsies River (+/- 600);

- Projects undergoing land-use management processes to be made available for social housing include Parow Precinct (+/- 360); and

- Further sub-precincts in Parow with a potential yield of +/- 1,000 are at scoping and pre-feasibility stage.

It is clear that the research in question not only severely underestimates Cape Town’s social housing pipeline, but is also misguided in its criticism of the location of certain social housing developments, such as those in Bellville, Belhar, Steenberg and elsewhere, which are all along development corridors and close to key economic nodes.

By the authors’ own admission, the research methodology used does not adequately account for economic activity — a key informant of the city’s spatial policy.

As a result, the authors incorrectly assume that the “core city” (areas within 5km of the CBD) contain most of the economic activity of a city.

Cape Town’s over-arching long-term spatial policy — the Municipal Spatial Development Framework (MSDF) — identifies an Urban Inner Core, comprising 17% of the metro area, where public investment is prioritised and where private sector investment is incentivised.

The policy also identifies environmentally protected areas, discouraged growth areas and “consolidation” areas, generally on the outskirts and of lesser priority at this stage.

The MSDF’s key objectives are to pursue a new spatial form that will ensure that Cape Town becomes a city that is more equitable, liveable, sustainable, resilient and efficient.

Within the Urban Inner Core, the primary road corridors that the city is targeting for transit-oriented development, are Voortrekker Road; Main Road in the southern suburbs; the R27, Marine Drive, Koeberg Road and Blaauwberg Road; Walter Sisulu and Govan Mbeki roads in Khayelitsha; AZ Berman Drive in Mitchells Plain; and Symphony Way towards Bellville.

Apart from transit corridors, public investment is aimed at key precincts within 500m of a rail or bus station, and at regenerating underperforming business districts.

It is noteworthy that the vast majority of social housing projects under construction, and those in planning, are all directly on or near centres of economic activities, or along well-located public transport routes. In tandem, the city has, from as early as 2009, pursued the release of the national government’s mega-properties for mixed-use development. This includes the inner city’s Culemborg; Wingfield along the Voortrekker corridor; Youngsfield in the south; and Ysterplaat, adjacent to Century City.

To date, the national Ministers of Human Settlements and Public Works seem to have made no progress in releasing the largest pieces of well-located land in Cape Town — signalling a lack of political commitment to enabling affordable housing. Many tens of thousands of opportunities are possible on these huge sites.

While the researchers have done a creditable overview of the national government’s failures around policy and grant-funding for the social housing programme over the years, since the Social Housing Act (2008), strangely, none of these details are mentioned in their Daily Maverick article.

The national government instituted various reforms to rationalise its housing subsidy structure in 2017, which has somewhat improved the viability of the social housing legislative framework.

However, it remains an extremely complex and time-consuming process to land viable social housing development. Grant funding remains inadequate at best, due to the mismanagement of resources at a national level. In fact, there is increasingly less grant funding to go around, with R118-million cut from the city’s Urban Settlements Development Grant last year alone.

Out of sustained commitment to expanding opportunity in key parts of the city, Cape Town has set out to align its full strategy suite to enable more well-located affordable housing — close to economic activity, along public transport routes.

Over the past decade, this includes the Integrated Transport Network Plan (2014) and Comprehensive Integrated Transport Plan (2018); the updated MSDF (2018); draft district spatial frameworks (2021) with public comment having closed on 6 June 2021; and the five-year Integrated Development Plans spanning this period.

Under the city’s new Human Settlements Strategy, recently approved by Council, all suitable municipal land continues to be assessed — from golf courses to mixed-use areas — to determine which of these properties could be developed for affordable housing, among other uses. A consolidated land pipeline will be developed to aid forward planning, including prioritised municipal land for well-located affordable housing.

It is an under-appreciated fact that the national zeitgeist is fundamentally moving away from the state as a primary provider of housing. This is being hastened by the drying up of grant funding.

Cape Town is alive to these realities and has thoroughly explored the opportunities available to the city in its various roles as provider, enabler and regulator.

Future affordable housing delivery will encompass a mix of:

- Upgrading informal settlements within an enabling environment for micro-developers;

- An enhanced toolkit of incentives for the private sector to deliver affordable housing, ranging from availing state land to reducing non-construction costs;

- Maximising the city’s enabling role as a land-use regulator, via an inclusionary housing policy, the cutting of red tape within municipal purview and advocacy for a more enabling national legislative framework; and

- partnerships with social housing institutions and other development agents to deliver affordable housing within mixed-use, cross-subsidised developments.

This level of forward thinking is vital, as funding for social housing from the national government is uncertain given the country’s precarious fiscal situation.

The city is responding proactively to this national context by innovating to ensure the long-term viability of well-located social housing. DM

Malusi Booi is Cape Town’s Mayoral Committee Member for Human Settlements.

Recent News

Here are recent news articles from the Building and Construction Industry.

Have you signed up for your free copy yet?